doença arterial periférica

SUMÁRIO

Arteriosclerose

É um termo geral que se refere ao endurecimento e espessamento das paredes arteriais. Existem dois principais tipos de arteriosclerose: aterosclerose e esclerose de Monckeberg.

Aterosclerose

Definição: É uma forma específica de arteriosclerose caracterizada pelo acúmulo de depósitos de lipídios (gordura), colesterol, cálcio e outras substâncias na camada íntima das artérias.

Efeito: Esse acúmulo, conhecido como placa aterosclerótica, pode estreitar ou obstruir as artérias, reduzindo o fluxo sanguíneo e aumentando o risco de eventos cardiovasculares, como infarto do miocárdio e acidente vascular cerebral (AVC).

Localização: Afeta principalmente artérias de grande e médio calibre, como as coronárias, carótidas e artérias periféricas.

Esclerose de Monckeberg

Definição: Também conhecida como esclerose medial calcificante, é uma forma de arteriosclerose que envolve a calcificação da camada média (túnica média) das artérias musculares.

Efeito: Ao contrário da aterosclerose, a esclerose de Monckeberg não causa estreitamento do lúmen arterial, mas pode levar a uma rigidez significativa da parede arterial.

Localização: É comum em pacientes idosos, com doença renal crônica, diabetes mellitus e doenças que causam calcificação vascular.

Consequência: Pode predispor à formação de aneurismas devido à rigidez das paredes arteriais.

Diferenças entre Monckeberg e Aterosclerose

- Arteriosclerose: Termo geral para o endurecimento das artérias.

- Aterosclerose: Acúmulo de placas lipídicas, colesterol e outras substâncias na camada íntima das artérias, levando ao estreitamento e obstrução.

- Esclerose de Monckeberg: Calcificação da camada média das artérias musculares, causando rigidez, mas sem estreitamento do lúmen.

Progressão da Aterosclerose

A aterosclerose é um processo crônico, sistêmico e progressivo que se inicia na juventude e é desencadeado por uma resposta inflamatória e fibroproliferativa. Sua fisiologia essencial começa na infância e é um processo contínuo que não pode ser totalmente interrompido, mas pode ser desacelerado ou gerenciado para evitar complicações. Isso é evidenciado pelas estrias gordurosas em crianças.

É importante notar que diferentes formas de aterosclerose podem coexistir no mesmo indivíduo. Essa complexidade ressalta o desafio do manejo da saúde cardiovascular e a necessidade de uma abordagem abrangente.

A aterosclerose prefere bifurcações arteriais, ângulos, artérias fixas e regiões posteriores das artérias. Nos pontos mais distantes das extremidades, assume um padrão circular.

A aterosclerose aumenta a permeabilidade da camada íntima às lipoproteínas, levando ao acúmulo de colesterol na parede vascular. Esse acúmulo, especialmente nas duas primeiras camadas, causa estenose. A adventícia, camada mais externa, geralmente é poupada. Quanto mais distal a lesão, pior o prognóstico, aumentando o risco de amputação.

O padrão de distribuição da aterosclerose varia conforme os fatores de risco.

- Tabagista sem hipertensão ou diabetes tende a ter aterosclerose na região aortoilíaca.

- Diabético exclusivo tende a apresentar aterosclerose no segmento infrapatelar

- Se a aterosclerose ocorre em todo o território arterial, o paciente geralmente é diabético, hipertenso e fumante.

Fatores de risco para aterosclerose

- Idade acima de 50 anos, principalmente acima de 70

- Hipercolesterolemia

- Tabagismo

- Hipertensão

- Diabetes

- Hiper-homocisteinemia (discreto)

- Fibrinogênio elevado (discreto)

Exame físico

- Diminuição de pelos nas pernas

- Hipotrofia muscular

- Palidez e vermelhidão reativa

- Gradiente térmico

- Ausência ou diminuição de pulsos

Índice Tornozelo-Braquial (ITB)

O Índice Tornozelo-Braquial (ITB) é um teste simples e não invasivo utilizado para avaliar a doença arterial periférica (DAP), uma condição em que as artérias das pernas ficam estreitadas ou bloqueadas devido à aterosclerose. O ITB compara a pressão arterial no tornozelo com a pressão arterial no braço para determinar a qualidade do fluxo sanguíneo nas pernas.

Como o ITB é Medido?

O teste do ITB envolve os seguintes passos:

Passo 1: Preparação do Paciente

- O paciente deve permanecer deitado em posição supina por pelo menos 5 minutos para garantir leituras precisas.

- Um dispositivo Doppler e manguitos de pressão arterial são utilizados para as medições.

Passo 2: Medição da Pressão Arterial

- A pressão arterial é medida em ambos os braços (artérias braquiais direita e esquerda) com um esfigmomanômetro e um transdutor Doppler.

- A pressão arterial é então medida em ambos os tornozelos (artéria dorsal do pé e artéria tibial posterior).

Passo 3: Cálculo do ITB

O ITB é calculado através da razão entre a maior pressão sistólica no tornozelo (artéria dorsal ou tibial posterior) e a maior pressão sistólica na artéria braquial.

Cada perna é avaliada separadamente.

Interpretação dos Resultados do ITB

- < 0,9 – Diagnóstico de doença arterial periférica

- < 0,7 – Claudicação

- < 0,5 – Viabilidade do membro ameaçada (ou pressão arterial sistólica < 40 mmHg)

- < 0,3 – Isquemia crítica

Importância Clínica do ITB

- Triagem para DAP: O ITB é útil para detectar DAP, mesmo em indivíduos assintomáticos.

- Avaliação do Risco Cardiovascular: A DAP está associada a um maior risco de infarto e AVC.

- Monitoramento da Progressão da Doença: O ITB pode acompanhar a piora ou melhora da condição ao longo do tempo.

- Orientação para Tratamento:

- Mudanças no Estilo de Vida: Parar de fumar, praticar exercícios e melhorar a alimentação.

- Medicamentos: Antiagregantes plaquetários, estatinas e anti-hipertensivos.

- Intervenções Cirúrgicas: Angioplastia ou cirurgia de revascularização em casos graves.

Limitações do ITB

- Pode estar falsamente elevado (>1,4) em pacientes com diabetes ou doença renal crônica devido à calcificação arterial.

- Não é confiável em casos de edema grave ou doença vascular extensa.

- Testes adicionais (como índice dedo-braquial (IDB), ultrassonografia Doppler ou angiografia) podem ser necessários para confirmação.

Quando o ITB Deve Ser Realizado?

- Pacientes com sintomas de DAP (ex.: dor ao caminhar, úlceras que não cicatrizam).

- Indivíduos com mais de 65 anos ou mais de 50 anos com fatores de risco (diabetes, tabagismo, hipertensão).

- Pacientes com doença cardiovascular conhecida (doença arterial coronariana ou cerebrovascular).

Claudicação intermitente

É um sinal característico da doença arterial periférica. Ocorre como dor muscular desencadeada pela atividade física e melhora com o repouso ou ao deixar o pé pendurado. Isso acontece porque, durante a atividade física, o membro precisa de mais sangue do que as artérias conseguem fornecer, levando à dor. Quando o paciente para ou abaixa o pé, a gravidade ajuda a melhorar a circulação, diminuindo a dor.

Isquemia crítica

É um estado clínico grave da doença arterial periférica, indicando risco de perda tecidual irreversível. Significa a presença de dores em repouso ou presença de lesão tecidual. Ocorre quando a pressão arterial sistólica nas artérias do tornozelo é abaixo de 40 mmHg ou abaixo de 60 mmHg quando há lesão trófica associada.

Dor em repouso

Na doença arterial periférica (DAP), a dor em repouso é um sinal de isquemia crítica, indicando um suprimento sanguíneo gravemente reduzido aos tecidos. Clássica e frequentemente, essa dor ocorre durante o período noturno, e isso está diretamente relacionado à queda fisiológica da pressão arterial enquanto dormimos.

Por que a Dor à Noite?

Durante o sono, há uma redução natural da pressão arterial devido à menor atividade do sistema nervoso simpático. Esse fenômeno é conhecido como queda noturna da pressão arterial (dipping fisiológico), e ocorre porque:

- O coração trabalha com menor demanda.

- Há uma diminuição no tônus vascular simpático.

- Ocorre menor resistência vascular periférica.

Em indivíduos saudáveis, essa queda pressórica não causa problemas, pois o fluxo sanguíneo ainda é suficiente para nutrir os tecidos. No entanto, em pacientes com DAP avançada, onde as artérias estão significativamente obstruídas, a queda da pressão arterial agrava a isquemia nos membros inferiores, levando à dor intensa, principalmente nos pés e dedos.

Características da Dor Noturna na DAP

- Localização: Ocorre mais frequentemente nos pés, dedos dos pés e calcanhares (regiões mais distais e vulneráveis à má perfusão).

- Tipo de Dor: Sensação de queimação ou dor profunda e intensa.

- Posição Aliviadora: Muitos pacientes relatam que a dor melhora ao deixar os pés pendentes para fora da cama, pois essa posição aumenta a pressão hidrostática e melhora o fluxo sanguíneo para os tecidos isquêmicos.

- Associação com Outras Lesões: Em casos mais graves, pode haver úlceras isquêmicas e necrose tecidual.

Sinais de Gravidade

A dor em repouso na DAP é um sinal alarmante de isquemia crítica e deve ser avaliada com urgência, pois indica que o membro afetado pode estar em risco de ulceração, gangrena e amputação. Além disso, esses pacientes geralmente apresentam um ABI (Índice Tornozelo-Braquial) ≤ 0,4, evidenciando um suprimento arterial extremamente reduzido.

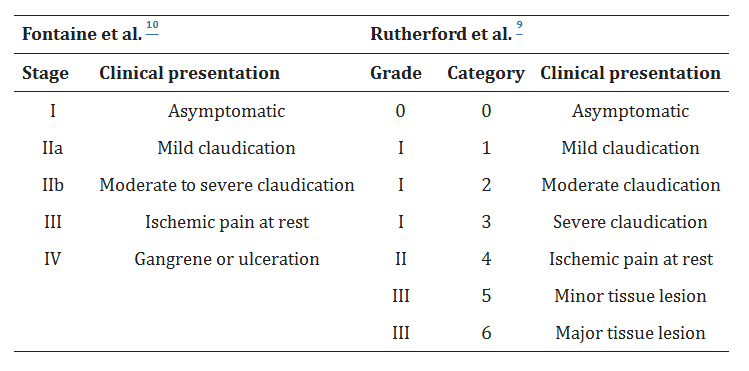

Classificação de Fontaine e Rutherford

Tratamento

Controle de todos os fatores de risco da doença aterosclerótica, principalmente com a suspensão do tabagismo:

- Suspender o tabagismo

- Controlar diabetes, hipertensão e hiperlipidemia

- Marcha programada

- Evitar o surgimento de lesões traumáticas em membros inferiores

Marcha Programada

A marcha programada é uma estratégia fundamental no tratamento da doença arterial periférica (DAP), especialmente em pacientes com claudicação intermitente (dor nas pernas ao caminhar devido à isquemia). Esse exercício estruturado melhora a capacidade funcional, reduz a dor e estimula a formação de circulação colateral, aumentando a perfusão sanguínea para os músculos.

Objetivo da Marcha Programada

- Melhorar a tolerância ao exercício e a distância percorrida antes da dor.

- Favorecer a formação de circulação colateral, compensando o fluxo arterial reduzido.

- Reduzir a inflamação sistêmica e melhorar o metabolismo muscular.

- Diminuir a progressão da doença e evitar complicações graves, como úlceras e amputações.

Como Deve Ser a Marcha Programada?

O programa de caminhada deve ser supervisionado por um profissional de saúde e seguir algumas diretrizes específicas:

A) Frequência

- 3 a 5 vezes por semana

- Sessões de 30 a 60 minutos por dia

- Duração mínima do programa: 12 semanas (para obter benefícios clínicos significativos)

B) Intensidade

- O paciente deve caminhar até sentir dor moderada a intensa (claudicação intermitente).

- Ao atingir esse limite, parar e descansar até a dor diminuir.

- Retomar a caminhada e repetir esse ciclo várias vezes.

C) Progressão Gradual

- O objetivo é aumentar progressivamente a distância percorrida antes do início da dor.

- Inicialmente, a caminhada pode ser mais curta e com maior número de pausas, mas ao longo das semanas, a resistência melhora.

- O paciente deve buscar aumentar o tempo total de caminhada e reduzir os intervalos de descanso.

Tipo de Terreno e Ambiente

- Idealmente, a marcha programada deve ser realizada em terreno plano para reduzir o impacto articular.

- Locais como esteiras ergométricas ou pistas de caminhada são recomendados.

- Caminhadas ao ar livre podem ser incentivadas, mas evitar subidas muito íngremes no início.

Benefícios da Marcha Programada

- Aumento da distância percorrida sem dor (pode dobrar ou triplicar após 6 meses de treinamento).

- Melhora da circulação colateral, promovendo maior fluxo sanguíneo para os músculos isquêmicos.

- Redução dos sintomas da claudicação intermitente, permitindo maior independência funcional.

- Melhoria da saúde cardiovascular geral, reduzindo riscos de infarto agudo do miocárdio.

- Controle dos fatores de risco como diabetes, hipertensão e dislipidemia.

Tratamento clínico

A melhor terapia médica para a doença arterial periférica (DAP) inclui uma combinação de terapia antiplaquetária, agentes redutores de lipídios, anti-hipertensivos e modificações no estilo de vida. Aqui está o regime farmacológico recomendado com doses:

Terapia Antiplaquetária

Para reduzir eventos cardiovasculares.

- AAS (Aspirina): 75–100 mg uma vez ao dia

- Clopidogrel: 75 mg uma vez ao dia (se a aspirina não for tolerada)

Para pacientes com DAP grave ou alto risco isquêmico (por exemplo, histórico de AVC, infarto do miocárdio ou múltiplos territórios vasculares afetados):

- Rivaroxabana (Xarelto) 2,5 mg duas vezes ao dia + AAS 100 mg uma vez ao dia

(com base no estudo COMPASS, que mostrou redução em eventos cardiovasculares maiores)

Hipolipemiantes

Para desacelerar a progressão da aterosclerose.

- Terapia com estatinas de alta intensidade (para todos os pacientes com DAP):

- Sinvastatina 40 mg uma vez ao dia

- Atorvastatina 40–80 mg uma vez ao dia

- Rosuvastatina 20–40 mg uma vez ao dia

(Meta: LDL-C < 55 mg/dL para pacientes de alto risco, conforme as diretrizes mais recentes)

Para pacientes que não atingem a meta de LDL apenas com estatinas, considerar:

- Ezetimiba 10 mg uma vez ao dia (associada à estatina)

- Inibidores de PCSK9 (por exemplo, Evolocumabe 140 mg a cada 2 semanas ou Alirocumabe 75–150 mg a cada 2 semanas)

Controle da Pressão Arterial

- Primeira linha: Inibidores da ECA ou BRAs (demonstraram reduzir eventos cardiovasculares na DAP)

- Ramipril 10 mg uma vez ao dia (benefício demonstrado no estudo HOPE)

- Losartana 50–100 mg uma vez ao dia

Se for necessário controle adicional, pode-se adicionar:

- Bloqueadores dos canais de cálcio (ex.: Amlodipina 5–10 mg uma vez ao dia)

- Diuréticos (ex.: Clortalidona 12,5–25 mg ao dia)

Controle Glicêmico

- Inibidores de SGLT2 (ex.: Empagliflozina 10–25 mg ao dia)

- Agonistas do receptor GLP-1 (ex.: Semaglutida 0,25–1 mg semanalmente)

Ambas as classes de medicamentos melhoram os desfechos cardiovasculares em pacientes com DAP e diabetes.

Alívio da Claudicação Intermitente

- Cilostazol 100 mg duas vezes ao dia (contraindicado em pacientes com insuficiência cardíaca)

(Melhora a distância de caminhada, mas não altera a progressão da doença.)

Alternativa:

- Pentoxifilina 400 mg três vezes ao dia (menos eficaz que o Cilostazol, raramente utilizada hoje em dia)

Cessação do Tabagismo

- Terapia de reposição de nicotina (adesivos, gomas)

- Vareniclina 0,5 mg uma vez ao dia por 3 dias, depois 1 mg duas vezes ao dia

- Bupropiona SR 150 mg uma vez ao dia por 3 dias, depois 150 mg duas vezes ao dia

Tratamento Cirúrgico

Indicado para pacientes com isquemia crítica (dores em repouso ou presença de lesão tecidual sem melhora) ou claudicação incapacitante sem resposta ao tratamento clínico.

Opções:

- Cirurgia tradicional

- Cirurgia endovascular

- Cirurgia híbrida

- Amputação primária

- Simpatectomia

- Neurotripsia

Classificação TASC

A classificação TASC (TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus) é um sistema utilizado para categorizar a gravidade das lesões arteriais em pacientes com doença arterial periférica (DAP). Essa classificação auxilia na tomada de decisões terapêuticas, indicando se o tratamento ideal é a revascularização por via endovascular ou cirurgia convencional.

Objetivo da Classificação TASC

- Padronizar o tratamento da doença arterial obstrutiva periférica.

- Direcionar a melhor estratégia terapêutica: tratamento clínico, angioplastia ou revascularização cirúrgica.

- Definir o prognóstico dos pacientes com DAP, considerando extensão, localização e severidade das lesões.

Estrutura da Classificação TASC

A classificação TASC divide as lesões arteriais em quatro categorias (A, B, C e D) com base no tamanho e número de obstruções.

- TASC A e B → Melhor prognóstico, indicadas para tratamento endovascular (angioplastia).

- TASC C e D → Lesões mais complexas, frequentemente requerendo cirurgia aberta para revascularização.

Classificação por Território Arterial

A Classificação TASC é aplicada em três territórios anatômicos:

- Aortoilíaco

- Femoropoplíteo

- Infrapatelar (artérias tibiais e fibular)

Cada território possui critérios próprios, considerando comprimento da estenose, número de lesões e envolvimento de artérias principais.

Classificação para Cada Território

TASC do Território Aortoilíaco

Lesões na aorta abdominal e artérias ilíacas.

| Classificação | Características |

|---|---|

| TASC A | Estenoses curtas (< 3 cm) em uma artéria ilíaca. |

| TASC B | Múltiplas estenoses curtas, estenose unilateral > 3 cm, ou oclusão curta (< 3 cm). |

| TASC C | Oclusões longas (> 3 cm) em uma ilíaca ou estenoses bilaterais longas. |

| TASC D | Oclusões bilaterais da artéria ilíaca comum ou oclusão extensa da aorta e ilíacas. |

TASC do Território Femoropoplíteo

Lesões na artéria femoral superficial e artéria poplítea.

| Classificação | Características |

|---|---|

| TASC A | Estenoses curtas (< 10 cm) ou oclusão única (< 5 cm). |

| TASC B | Múltiplas estenoses ≤ 5 cm ou oclusão ≤ 15 cm sem envolvimento da artéria poplítea. |

| TASC C | Múltiplas estenoses ou oclusões > 15 cm. |

| TASC D | Oclusão da artéria femoral comum ou oclusões longas (> 20 cm), incluindo poplítea. |

TASC do Território Infrapatelar

Lesões nas artérias tibiais anterior, posterior e fibular.

| Classificação | Características |

|---|---|

| TASC A | Estenose única < 5 cm. |

| TASC B | Múltiplas estenoses curtas (< 5 cm) somando > 10 cm ou oclusão < 3 cm. |

| TASC C | Múltiplas estenoses e oclusões > 10 cm. |

| TASC D | Oclusões longas com calcificação intensa e sem circulação colateral. |

Resumo

- TASC A → Estenoses curtas, preferência por angioplastia.

- TASC B → Estenoses múltiplas curtas, angioplastia ainda é viável.

- TASC C → Estenoses e oclusões longas, cirurgia pode ser melhor.

- TASC D → Oclusões complexas, cirurgia quase sempre necessária.

Tabela da classificação de TASC